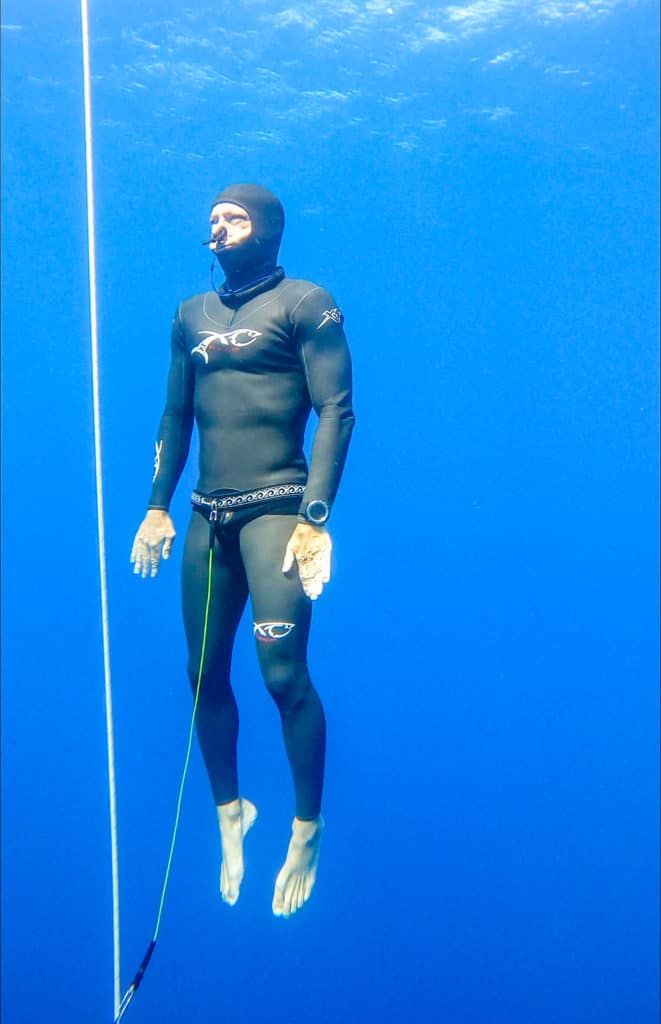

Tom Peled has been diving since 1989 as a dive instructor, commercial diver, and now a freediving breath-hold coach. He specializes in breath and body work for stress anxiety and trauma and has worked with injured veterans. His extensive diving experience extended to training Navy Seals and airforce rescue units in Israel.

Tell us about your journey into freediving.

I have grown up in and around the sea and always felt a good connection with water. I had been a scuba diving instructor since 1998 after diving in the navy for a few years. Then I became a cave diver, tech, and rebreather instructor and during those years I never gave freediving a second thought.

When I finally went and did the freediving course, it took over me completely like I was 16 again.

I clearly remember promising to myself and anybody else who was willing to listen, that I was only going to do freediving for my own personal experience. And that I will not become an instructor, teach, or compete in freediving. However, I broke this promise a long time ago!

I did become an instructor and started competing all over the world. More importantly, this journey made me an explorer, igniting my curiosity regarding everything to do with mind, body, and performance.

Eventually, I also became a breath coach and started working with people out of the water as well and I combine those two fields today in everything I do.

Can you explain some of the freediving disciplines?

I teach all disciplines in freediving. The most challenging is definitely the No Fins discipline. It is the most physically demanding and technically challenging as you don’t have any means of propulsion other than your legs and arms and you are moving in a natural breaststroke.

In terms of efficiency, meaning the amount of energy you have to put to move your body through the water, you get the least value in comparison to using long bi-fins, a big monofin, or even by pulling on the line.

Bigger effort means higher oxygen consumption and faster CO2 buildup. Technically you have to be at least a decent swimmer for this discipline. Without proper technique, it would mean being even less efficient and that would make the dive too difficult.

The easiest discipline especially for beginners is Free Immersion which is when you pull on the line to get to depth and back to the surface.

What are some of the most common concerns with new freedivers? How do they overcome these concerns?

Most newcomers to freediving are concerned with their breath-hold time. They are afraid it won’t be enough to get to depth. In fact, breath-hold capabilities are hardly ever the limiting factor during the basic courses.

The first few things you learn in freediving is the mental aspect of breath-hold, proper breathing, and how to better understand your body’s signs when holding your breath. Once these are covered everybody’s breath-hold improves dramatically.

Can you explain some breathing techniques that you teach?

As part of the preparation for a dive, we use a breathing technique that facilitates relaxation and helps us stay mentally calm and focused. It is based on three simple principles.

The first aspect is belly breathing. This is where you want your diaphragm to do most of the breathing motion below your rib cage and have as little motion as possible higher in the chest area.

Second, use a constant breathing tempo or pace. This will generate mental focus through heart rate regulation.

Third, extend the exhale to be longer than the inhale part of the breath. A classic parasympathetic (relaxed) breathing is at about 1:1.5 ratio, for example 4 seconds inhale to 6 seconds exhale.

With time and practice, you should find the volume and pace that fits you best.

Can you describe what happens to our bodies when we breath-hold?

Our ability to hold our breath is based on a physiological mechanism that is called the mammalian dive reflex. Try to think of it as what your cell phone does when it goes to battery saving mode when it gets low.

The phone will shut down all unnecessary apps, bringing down the screen brightness, and will lower its overall activity to save power consumption. Our body will do the same to conserve oxygen and make sure to prioritize the brain with the oxygen it has.

This process starts even before we hold our breath, and as soon as we touch the water and get out faces wet. So it happens partly even when we do not hold our breath, for example when scuba diving or snorkeling.

The first 3 changes happen almost immediately as we get in the water; our heart rate will slow down, blood vessels in the extremities will constrict and we will feel the need to urinate (yeah, that’s why it happens) in order to lower the blood volume.

As we get longer into the breath-hold our heart rate will keep going down. In trained divers, it has been documented going below 30 BPM (beats per minute). Whereas the usual range for a resting heart rate is anywhere between 60 and 90 BPM.

Next, we get blood shift. This is when the body gathers the blood from the extremities and unnecessary organs, and brings it to the upper torso to flood the lungs and mostly conserve the oxygen for the brain.

The final part is a spleen contraction or squeeze that releases extra oxygen-rich red blood cells to the bloodstream and adds them to circulation.

Our physiology is pretty awesome and the body knows exactly what to do. We just need to trust it.

What are some of the risks involved in breath-holding?

Blackouts are the obvious and primary risk when freediving. This will occur when our oxygen level becomes too low and gets to about 50%.

We minimize the risks first through training and education. The better part of the basic courses should be dedicated to safety.

- We teach relaxation

- Learning to recognize the physiological signs during breath-hold to guide us as a “road map”

- Proper recovery at the end of a breath-hold which is very important

- Using safety gear

- And most importantly, diving with a buddy and how to be a buddy/safety diver.

When the course is complete, a diver should be able to know how to dive within their limits, what is the proper progression in this sport, and to never ever dive alone.

How can we use breathing techniques to deal with some of the stresses in our everyday lives?

Breathing is our most effective stress regulator. We have different breathing patterns for higher stress and demanding activities and for rest and relaxation. Learning these patterns and how to adjust them is not only key for lowering chronic stress in our life but also to be able to perform on a higher level under acute stress situations.

There are 2 levels of breathwork to mitigate stress. One is breathing exercises you can do once or twice a day or just whenever you feel like you need to. The other, deeper level is changing your functional day to day, minute to minute, breathing pattern.

Basic breathing for relaxation is slow belly (diaphragm) breathing through the nose with an extended exhale and a short pause at the end before taking the next inhale.

How do our land habits affect our abilities underwater? Are there things we should avoid or do more of?

Since we use the same body underwater as we use on land, every physical aspect affects our diving capabilities, so everything concerning a healthy lifestyle is recommended for divers as well, for example; fitness and diet. I would however emphasize a few things for divers:

- Prioritize sleep, especially before a diving day. This alone could make the biggest difference between an enjoyable and relaxed experience and making unnecessary mistakes, feeling uncomfortable, confused, stressed, and even seasick.

- Hydration is key. Not just in general, and not only for decompression reasons but also for equalization. Not many people know this but being dehydrated will damper your equalization.

- Try to reduce foods that make us produce mucus and phlegm like dairy, peanuts, and bananas.

- Learn to breath

What is your mindset when you are freediving?

I aspire to be in a mindset which I describe as focused relaxation. It is often called referred to as “flow” state. This is when every action is being carried naturally and accurately by the body while the mind is free to focus only on what you choose.

I keep my concentration on my body and on a positive outcome. Before the dive my breathing will be the center of attention and once I begin the dive, I will move it to one area of the body I want to soften or relax. With this I keep my focus on a positive outcome or success. Other helpful mental tools can be positive internal dialog, a distant outside-like observation, or using mantras.

What has been your most rewarding experience as a freediving instructor?

I often get to work with people who are afraid of water or the sea. It is actually surprising how many surfers and even swimmers suffer from anxiety when it comes to deep water and the open sea. A lot of times this is due to past trauma. It is always a great satisfaction to watch them achieve a breakthrough.

The last case I can vividly remember was with an open water swim coach. She had a near-drowning incident while scuba diving almost 20 years before that. For many years she could not get in the water. Even after she went back to swimming and coaching in the open sea, she couldn’t get herself to dive or even snorkel again, not to mention holding her breath underwater. We had some ups and downs during training but overall she did totally fine until the last day, where it was not only going to be deeper but also at the same dive site where she had her accident 20 years before.

It started bad, and she was not able to control her emotions at first, but gradually she overcame them using the tools she received in the course. Finally, when we dove together down to 17 meters, I could see tears of joy and relief form in her mask. These are the rewards we work for…Continue reading

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.